When the Creative Commons forged a more progressive look copyright law, enabling content creators legal power to elect specific use of their works, a cultural movement ensued. Until that point, copyright law reflected a historical component of intellectual property protection vital to commercial endeavors, but presented obstacles to reuse. Any of the various combinations of the Creative Commons license permit specific opportunities to a consumer of the assets, turning copyright into a layman’s device, clarifying for both creator and consumer a license that is compressible and deliberate. Copyright doe not mean “don’t use,” it just presents additional barriers because it lacks the varietal nature of the Creative Commons. Copyright is very specific, that the author of the content holds all rights and in order to use it, one would need to contact the author for permission or license. This appears to be a great inhibitor and makes a great compliment to the more explicit Creative Commons licenses. As the Creative Commons site explains, “Creative Commons defines the spectrum of possibilities between full copyright — all rights reserved — and the public domain — no rights reserved.â€

So, while it is possible to permit some level of sharing and remixing in the end the license still reserves rights to the work. Copyright on the other hand reserves all rights. In cases where you want to know and be in control of your work, copyright is what you want.

While people tend to understand that they usually own the copyright of their creations, they do not realize the limitations of restitution if the work is not registered. Specifically in the United States, failing to register your work limits the amount of damages one can seek or be awarded in court. While my living is not made based on my photography, I have chosen to explicitly copyright my work, which includes registering it with the U.S. Copyright Office.

Several sites discuss how to do register work with the U.S. Copyright Office. (e.g. ASMP and Peter Krogh) More recently, there is a great series that Photoshop User Magazine is running, “The Copyright Zone†and some great posts over at Scott Kelby’s blog.

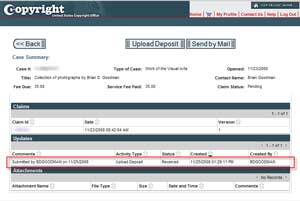

The online copyright registration tool is your typical solution that was constructed to the letter of the requirements, which is to say that most people will find it rigid and cryptic. There is a lot of documentation to help bolster your confidence, but at some point, you simply need to take the plunge. Here are three tips that made my life much simpler.

First, if you decide to upload your work, you are sure to notice the warnings of 30 minutes per upload. This might cause some panic depending on your connection to the Internet, but you need not be concerned. Interestingly enough, no one mentions that you can upload many times. In practice, this means any specific upload is limited to 30 minutes, but you can continue to upload as many times as is required to transfer your collection. Each upload is logged and displayed as part of your submission. It takes a few minutes for the system to show each transaction (my guess is they scan for malicious code), but if you do not see your uploaded work, then they never received it. You can call or email for verification or upload again to make sure. For those of us registering an entire years worth of unpublished work, this is important!

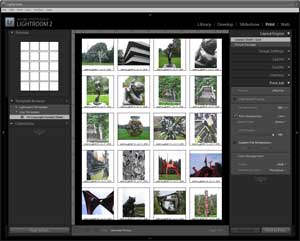

Second, you will read about the format of submission. Some people advocate for individual images and yet others talk about contact sheets. Having called the U.S. Copyright Office for guidance, apparently, a digital contact sheet is acceptable. This really simplifies the registration of unpublished works. I used Adobe Lightroom v2 to generate digital contact sheets (4 columns, 5 rows) with the filename and date taken under each image. All the guidance says that the image needs to be clearly visible on small displays. I chose to export at 300 dpi and in JPG format. At 300 dpi the contact sheet will effectively show 20 images to a page while allowing the individual image to render beautifully at over 580 pixels in the longest dimension. Digital contact sheets allow for fewer uploads, while presenting the work in high quality legible form. If you are a Lightroom user, you are welcome to the template I used.

Third, the online copyright registration site recommends using ZIP compression as a means of uploading many files. While using zip on JPEGs yields less space savings than on other files, I used it to simplify my uploading. I numbered them 1 of X to ensure my logic was clear. Additionally, this will allow a copyright examiner to reconcile uploads just in case I submitted an archive twice. Finally, WinZip is offering aggressive compression mechanisms, specifically for images. I used legacy compression to ensure compatibility. Compression programs have come a long way, but in this case, interoperability was the priority.

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer. My comments here are a documentation of how I approached registering photographic works and may not apply for your use. Please consult an IP lawyer or the U.S. Copyright office if you want to verify you are following acceptable procedures.